VC Compensation 101: Fees, Carry, and Aligned Incentives

A clear breakdown of VC compensation, showing how fund size, fees, and carry shape incentives, behavior, and decision-making inside venture firms.

Introduction

When people talk about VC compensation, they usually focus on the headline numbers: base salary, bonus, total comp.

That’s understandable, but it’s also misleading.

What actually drives behavior in venture is how compensation is constructed. In particular, the balance between management fees and carry does a remarkably good job predicting how a fund behaves in the real world.

So instead of debating whether VCs make “too much” or “too little,” let’s walk through the math that quietly shapes incentives.

The Only Two Ways a VC Firm Makes Money

Before we get into fund sizes and roles, it’s worth grounding ourselves in first principles.

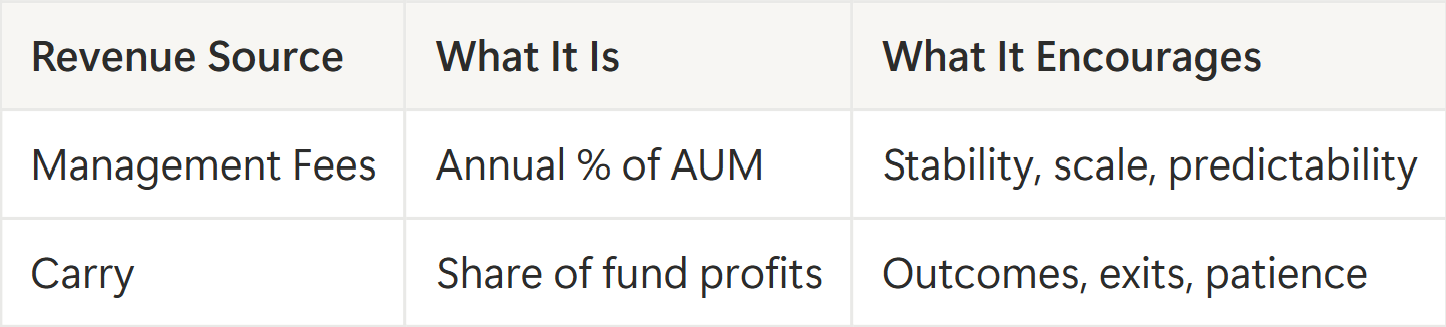

Every VC firm earns money in exactly two ways:

Everything else… salary, bonus, distributions, etc... is just a way of allocating these two streams.

Once you see that, the rest of the story starts to fall into place.

Why Fund Size Changes the Conversation

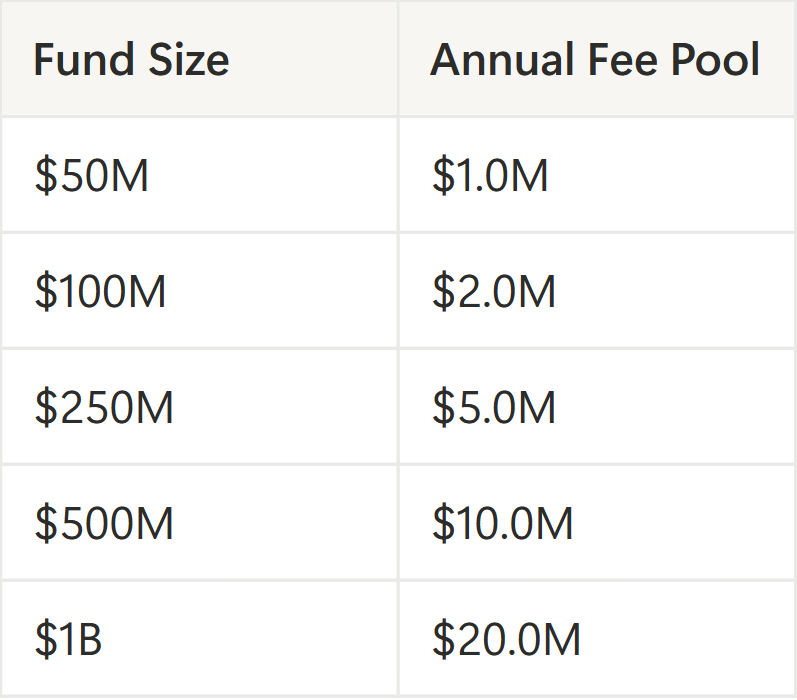

Fees scale linearly with assets. Costs don’t.

That simple fact is why a $100M fund and a $1B fund can’t and shouldn’t behave the same way.

Let’s start with the fee side.

Management Fees by Fund Size (2% Assumption)

At a glance, this explains a lot.

A $50M to $100M fund has just enough fee revenue to cover a small team and basic operations. A $1B fund can support partners, juniors, platform staff, and still have room to breathe.

But fees alone don’t tell the full story, so let’s look at what they actually have to cover.

What Fees Really Pay For

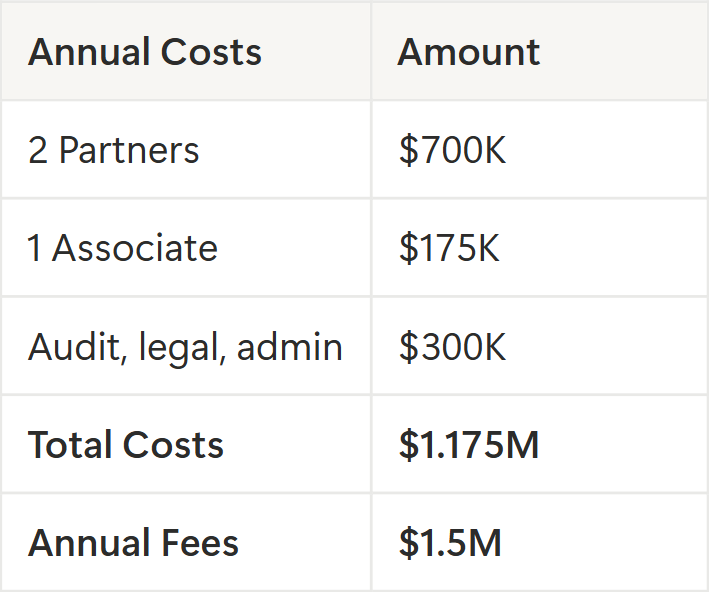

Now we subtract the boring but unavoidable stuff: people and overhead.

Example: $75M Early-Stage Fund

What’s left is a thin margin.

In this world, fees keep the lights on, but carry is where the upside (and often the stress) lives.

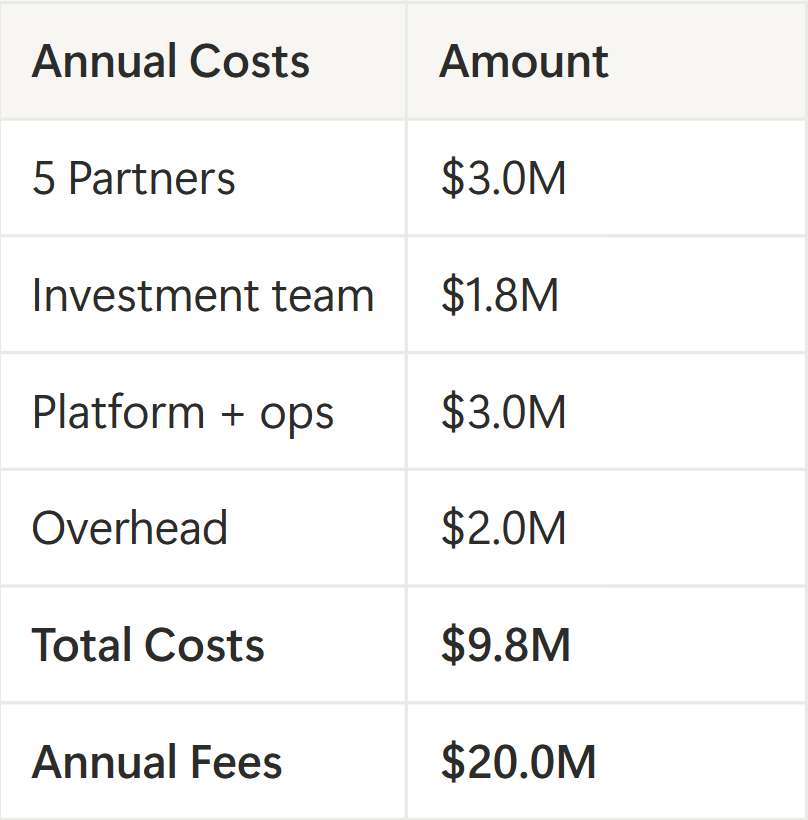

Now compare that to a larger fund.

Example: $1B Fund

Here, fees don’t just sustain the firm, they define it. Carry still matters, but it’s no longer existential.

This is the first big inflection point.

Where Carry Comes In

Once fees cover survival, carry becomes optional. Before that, it’s everything.

Carry only shows up if a fund clears its hurdle and returns real profits, so let’s look at what that pool actually looks like.

Let’s use a simple, illustrative example.

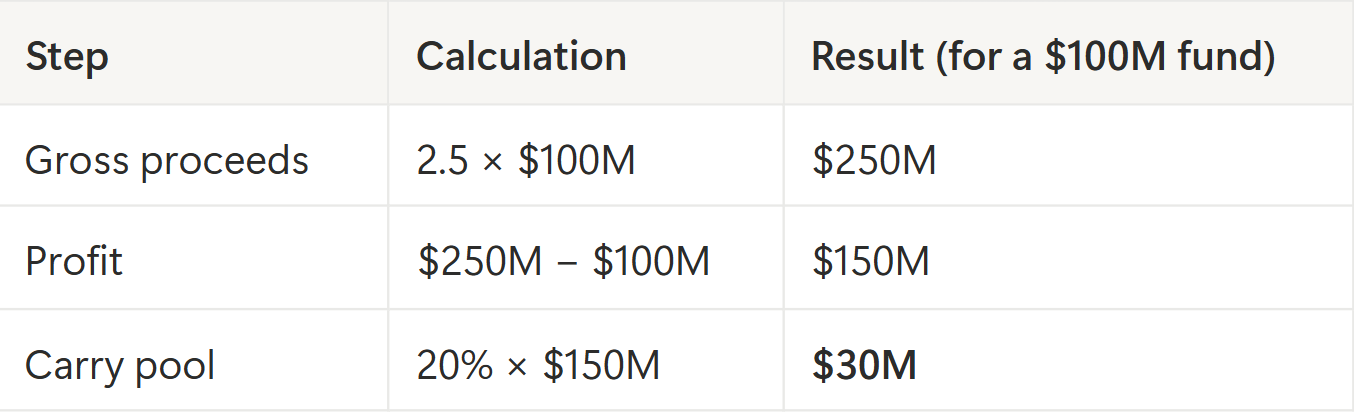

Assumptions:

- 20% carry

- 2.5× gross fund return

How the Carry Pool Is Created

At a 2.5× return, profits equal 1.5× invested capital. With a standard 20% carry, that means the total carry pool equals roughly 30% of fund size.

Once you see that, scaling becomes intuitive.

- A $50M fund produces ~$15M of total carry

- A $100M fund produces ~$30M

- A $1B fund produces ~$300M

These numbers look large—and they are—but they’re spread across years, partners, and vesting schedules. To understand incentives, we have to bring it down to the individual level.

Let’s keep things simple and assume equal splits.

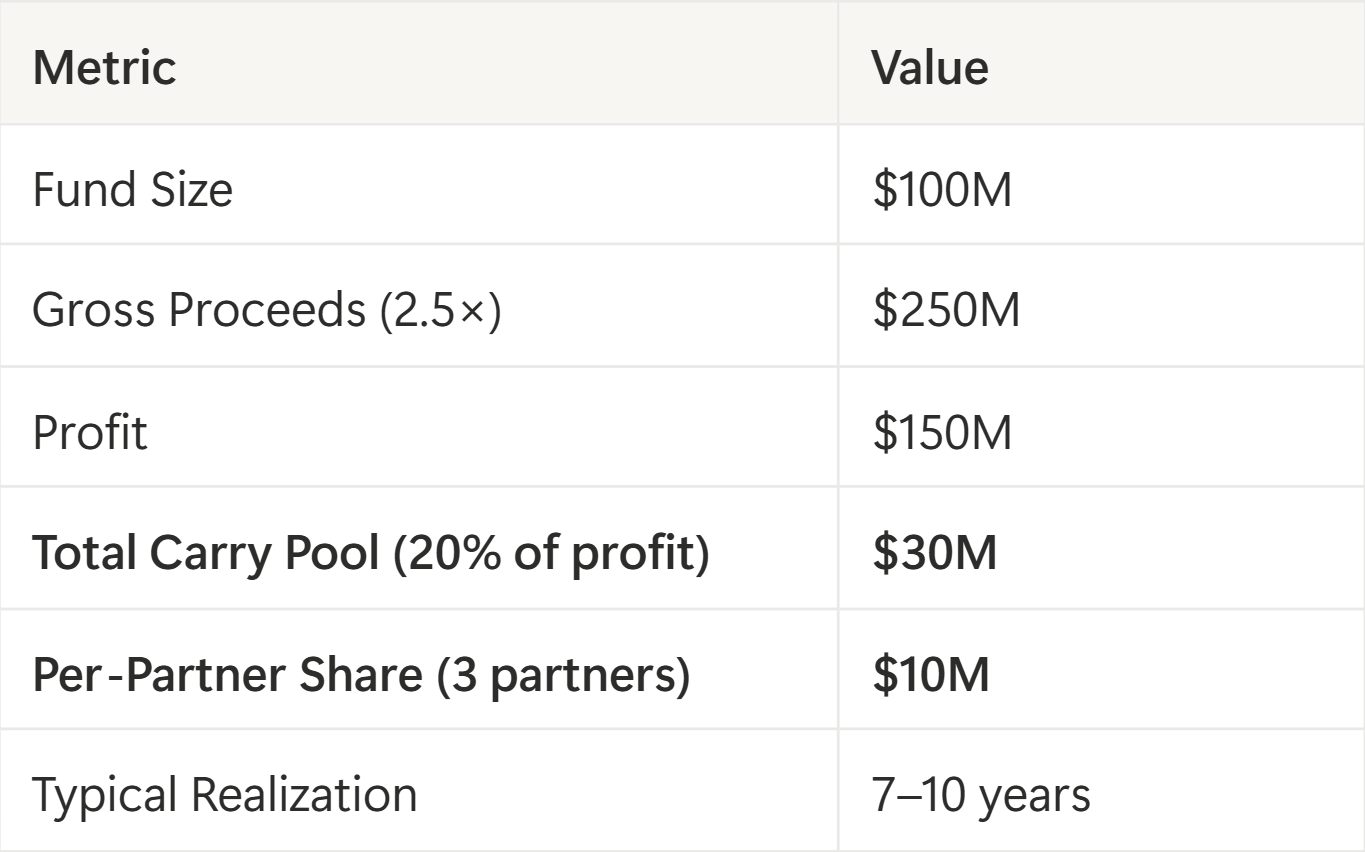

Small Fund: $100M Fund, 3 Partners

In a small fund, this carry can easily exceed lifetime salary from fees. That’s why ownership, pacing, and exits stay front and center.

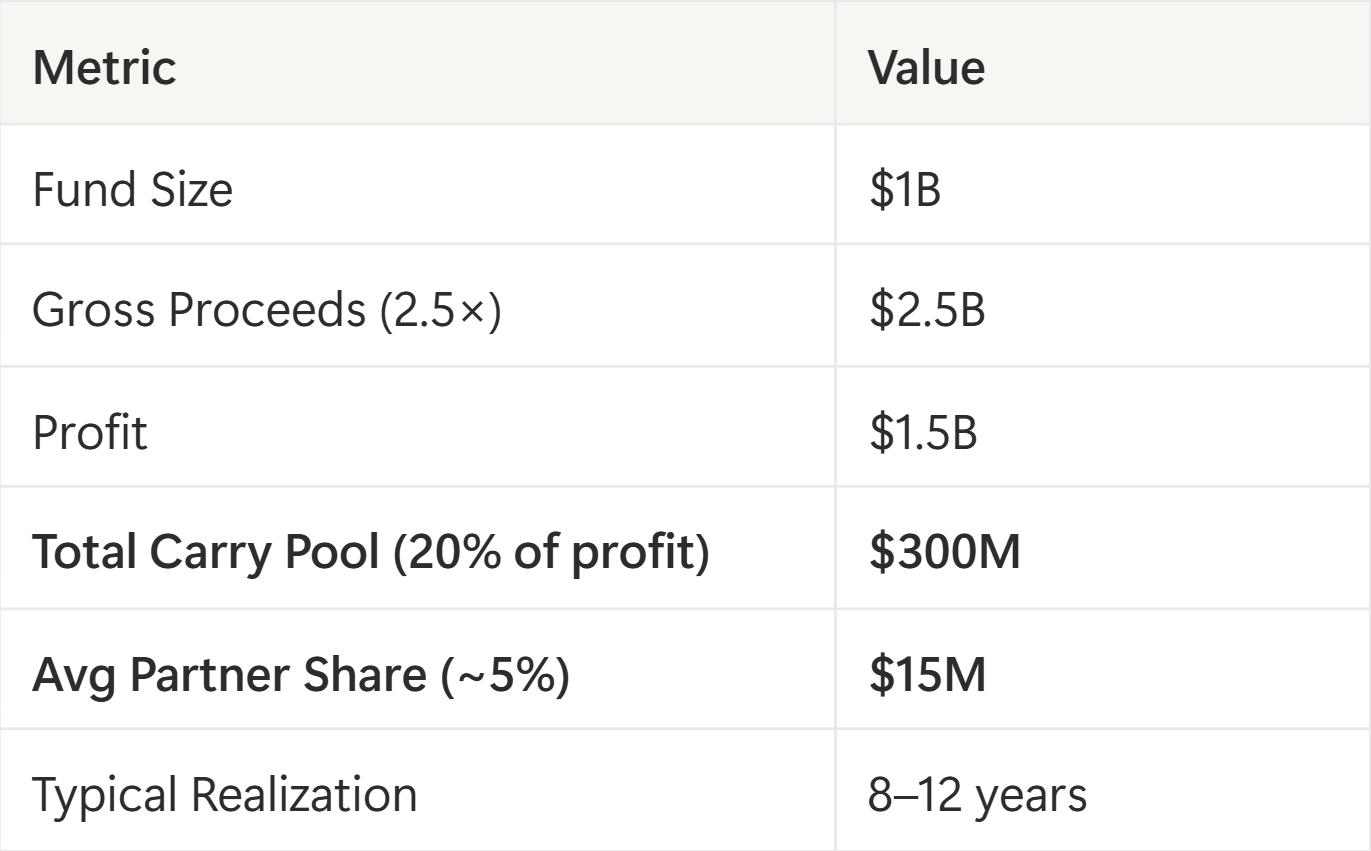

Large Fund: $1B Fund, 8 Partners

Meaningful upside, but often not required for financial stability along the way.

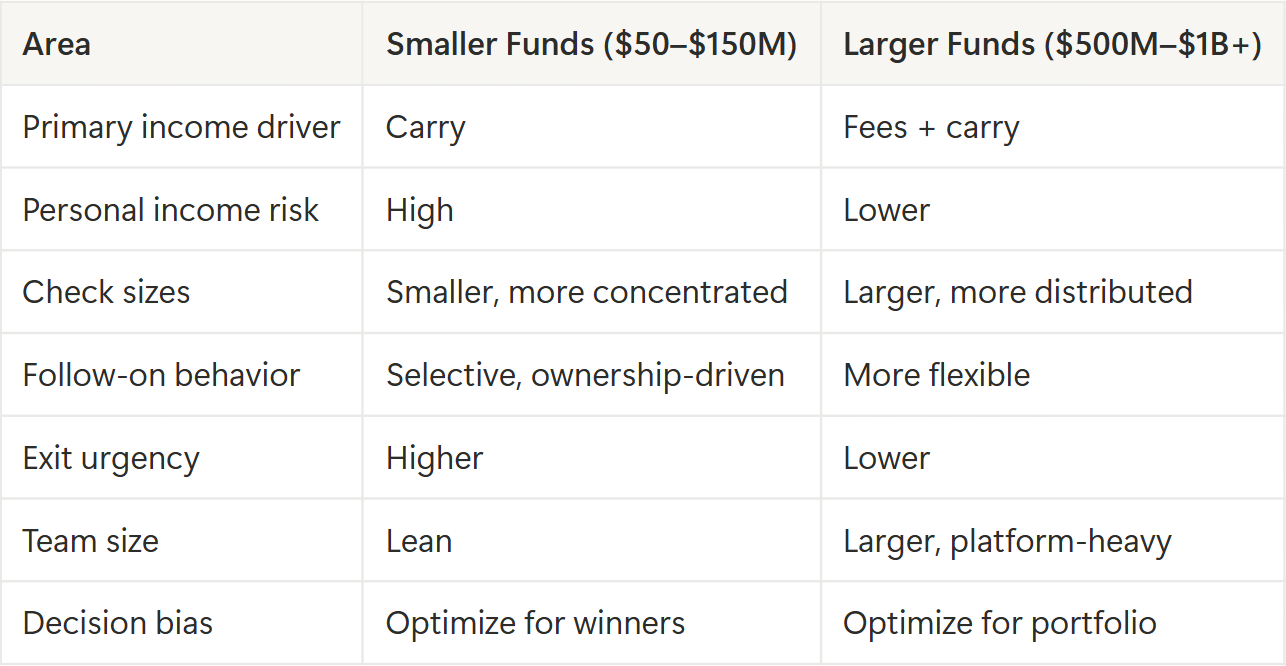

How This Shows Up in Practice

Once you understand the fee-to-carry ratio, the behavioral differences stop looking philosophical and start looking structural.

Smaller funds are not “hungrier” because partners are wired differently. They’re hungrier because fees barely cover survival and carry is the only path to meaningful upside.

Larger funds aren’t slower or more conservative because they lack ambition. They’re slower because fees already provide financial stability, which naturally dampens urgency around outcomes.

What This Means for Emerging Managers

Assume fees only cover survival. At small fund sizes, 2% keeps the firm running. Don’t plan your life around it.

Design everything around carry actually paying off. If a good fund outcome wouldn’t materially change your personal finances, incentives will drift.

Expect a long gap before outcomes show up. If you’re not okay waiting years for carry, the model will feel broken even when it’s working.

Be explicit with LPs early. Walk through how fees, pay, and carry really work — and write it clearly into the LPA.

Know what kind of risk you’re signing up for. Small funds feel much closer to being a founder than an employee.

If you’re an emerging manager thinking through these tradeoffs, David Zhou shares a lot of practical, real-world tactics on building LP relationships and raising early funds on the How I Raised It podcast. It’s a useful companion to the incentive math above.